Syrinx Music

Tanner, Mark: Creature Comforts, Book 1. Flute & Piano - Digital Download

Tanner, Mark: Creature Comforts, Book 1. Flute & Piano - Digital Download

Couldn't load pickup availability

Contents

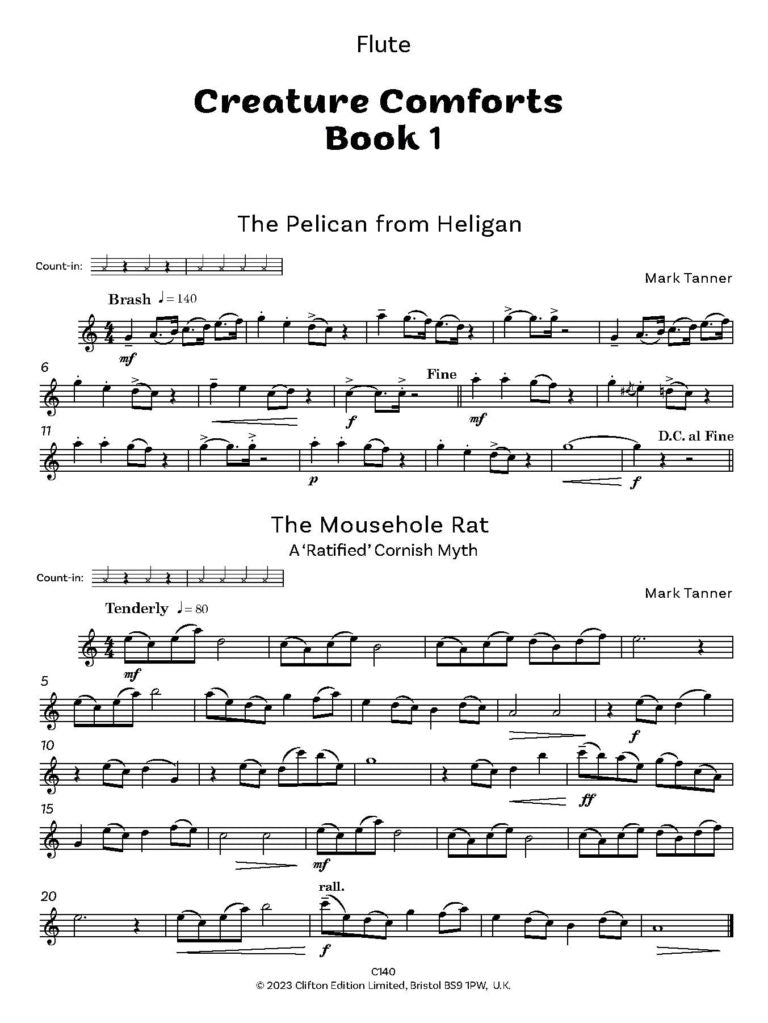

1 The Pelican from Heligan

2 The Mousehole Rat

3 The Slothful Sloth

4 My Camel’s got the Hump

5 Crocodile Tears

6 Meerkat Market

7 Cormorant High

8 Blu Gnu

9 There’s a Black Widow on my Banana

10 Your Weasel’s got Measles

11 One Leg fell off my Donkey

12 Gerbil’s Great Escape

13 A Fish can Whistle

14 The Mysterious Affair at Badger’s Cross

15 Tangaroo

Foreword

Creature Comforts: animal–inspired pieces for flute & piano is currently published in two volumes: grades 1—3 and grades 4–6. There is an enjoyable array of moods and styles to conjure with here, although the common denominator — creatures, great and small — is a theme that I’m hoping you will relate to easily. The pieces are arrangements from a series called Eye–Tunes, originally published by Spartan Press. A number of the pieces have been road–tested countless times in recitals (for example, The Moth Collector received its debut as an encore at Wigmore Hall in 2009) — indeed their consistently positive reception as wholesome, ‘proper’ pieces has led naturally to these albums aimed at the early and intermediate flautist.

As with the piano versions, the titles of the pieces are crucial in suggesting musical character, and I must once again thank Gillian Poznansky for dreaming up many of the more memorable ones; Gillian also oversaw the score editing process and helped to ensure the preparation of an album that embraces pieces of an appropriate technical level, set in suitable keys etc.

Musical spirit

Clues to the overall spirit of the music often spill over from the piano accompaniments. Hence teachers should look beyond the surface details in the flute parts to gain a fuller awareness of the sound–world of each piece. ‘Swing’ rhythms are perhaps best thought of as lying somewhere between dotted and triplet figures — in other words, rhythm without a straitjacket. Again, look to the piano parts for assistance here, as these are likely to be highly suggestive. Details of dynamics and articulation are central to lending phrases a sense of progression — search out the high–points, particularly in longer cantabile lines where sensible breathing places become even more important, and bear in mind that subtle alterations to the speed often affect where you breathe, too. Likewise, follow your nose when it comes to making sense of other score markings — your own instincts are potentially as worthy as the composer’s(!) — and only by experimenting with different ways of doing things can you discover what sits most comfortably. On this note, don’t stress unduly about the metronome marks, which are only intended to be a guide, not a rod for your back. Although buoyancy is a key attribute (in slow music as well as fast), rarely is this achieved through speed alone.

Ensemble playing

It is often best for flautists to conquer their parts in isolation, rather than to attempt to follow a pianist’s optimistic tempo from day one. The tune is frequently shared by the piano part, so bear in mind that bars rest are only temporary pauses in your part — the music carries on, even when you’ve paused, and you need to be aware of what is going on within the overall musical canvas. Ensembles rarely spend sufficient time rehearsing the links between sections, or the passing of the musical baton to and fro, and yet it is here that things typically go skew–whiff in the heat of a performance. So, why not practise starting (and restarting) in sensible places within the music, not just at the beginning.

Building a sense of performance

Practice rarely makes perfect, but it will usually make the all–important difference. Be flexible in your approach, and as I’ve written elsewhere, roll up your sleeves and have fun with these pieces. “The devil is in the detail”, so they say, and this means going beyond the obvious and delving into your own imagination. Care about your sound, care about ends of phrases, and most of all, care about putting smiles on your audience’s faces; after all, they’re the people who throw roses at your feet when you play nicely (or tomatoes when you don’t). It’s your job to keep them awake, not the composer’s (he’s already done his bit), and this can only be achieved by presenting yourself on stage as confidently as a double–glazing salesman at your front door. The art of performance isn’t so different from composition, when you stop to think about it — the black marks etched onto the page represent the composer’s best attempts at communicating something to you, whereas in a performance it falls on you to communicate something memorable on the spur of the moment to your audience. Neither role can succeed without some understanding of the other. Present your performance as something precious that comes from inside you; it might only last a minute or two, but if you do it well you can bring a tear to the vicar’s eye and a proud smile to granny’s face — so give generously; it’s well worth your effort.

Backing tracks

Backing tracks are free to download (see back cover) and will permit run–throughs and performances in situations that cannot accommodate a piano, which is an ever–present reality for teachers operating in small spaces with a ghetto–blaster. Unlike a number of backing tracks included in similar books, which are essentially computer MIDI files rendered into audio files, these are real piano parts recorded independently from the flute and piano performances. Hence they are not ‘quantised’, which means that a certain degree of flexibility has been built into the playing that, one hopes, will lead to more musical, less mechanical playing. Tempo clicks have been put in, generally at the start of tracks, but only where there isn’t a piano introduction to set the pace, and these have been marked into the scores. A few of the faster pieces also have slower versions to alleviate the difficulties one might encounter early in the learning process. Furthermore, these days, a variety of tempo–changing software packages are freely downloadable, which will allow you to slow down (or indeed, speed up) backing tracks without altering the pitch, so you might want to experiment with these. Ultimately though, playing with a living, breathing pianist lies at the heart of profitable music–making, and the all–important sense of communication between you and your audience actually starts when you and your accompanist are able to dovetail your ideas.

Bon voyage,

Share